The heart of Digital Mobility Platforms: Journey Planning Configuration

This is the third of a short series of articles that aims to try to better define the requirements, limitations and pitfalls to avoid when delivering Digital Mobility Platforms (DMPs), previously referred to as MaaS, within a devolved UK transport environment.

As per the first article, there are examples of great practice around the world and there are even a couple of examples from the UK, but it must be acknowledged that the current devolved and decentralised transport landscape in the UK does make the delivery of any type of integrated transport more challenging.

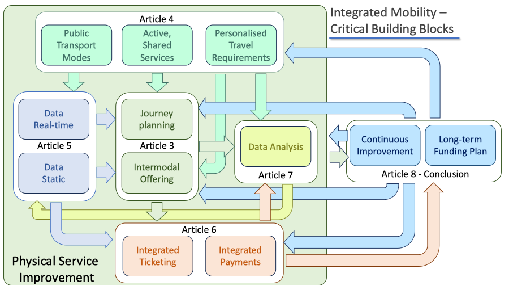

This blog builds on the approach identified in the previous one and will concentrate on a specific DMP element as identified in the graphic above – Journey Planning and the Intermodal Offering.

In this article, we will drill down into requirements to consider for two major DMP elements, Journey Planning and selecting modal choice, both of which in my view are inter-related. We will look at traditional Journey Planning core requirements as well as some elements of personalisation that are needed for core features for Journey Planning to function correctly.

Exploring Journey Planning

It is not the intention of this or subsequent articles to provide information relating to every element identified in each of these matrices – some should be reasonably well understood, and additional detail can be added to this series as needed and time allows. If after reading this, you feel that there needs to be further definition around any element, then please drop me a line and I’ll add the additional more detail and content.

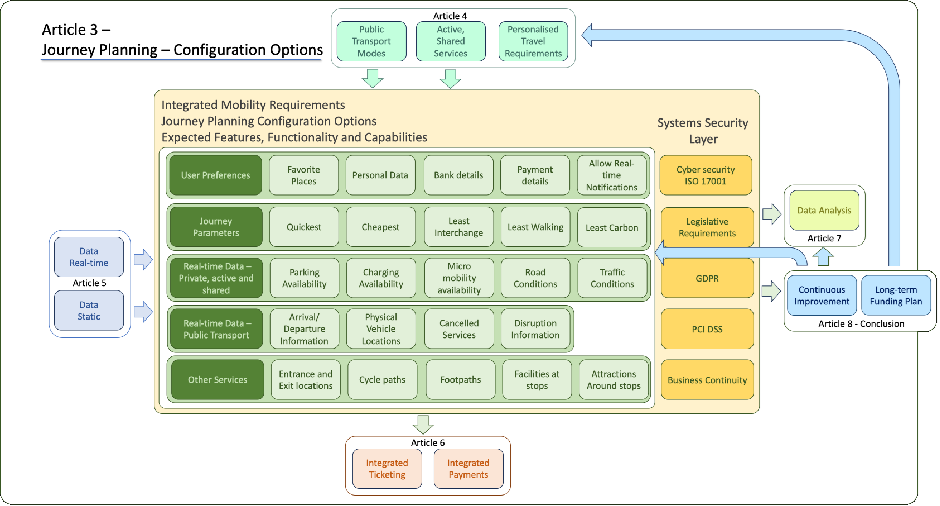

Above you can see the core elements of Journey Planning identified. There is far more detail that can be identified, for example, Favourite Places would require the ability to store, save, update, delete, change, share, track, get alerts, notifications etc.

Likewise, Payment details, should allow the user to store multiple payment options, and provide for them the ability to edit, delete, and/or freeze them. It may also allow for split payments, or recurring payments.

System Security Layer

Before starting to define your DMP, it is essential to identify how you will keep your system and systems data (some of which will be quite sensitive) safe and secure. For this reason, you must define your approach to data security and management. And define whether you as an authority want to be the data controller, the data processor, or want no access to any customer data. You will also need to understand what data will need to be shared and with whom, and the implications of those decisions. But please be aware that some of this data may well have previously been collected by your transport operators, who may be reluctant to lose access to customer data which could otherwise be used for promotions or systems analysis.

Too many DMPs fail not because of the technology, but because of human factors, and the perception that one stakeholder or another is either losing something or getting an unfair advantage. It is definitely worth having those discussions sooner rather than later, and demonstrating non-bias, cost neutrality, customer data retention and where possible highlighting that the DMP provides an “additional” sales channel and would not detract from the systems and services that currently exist.

Some platform providers may not be ISO17001 accredited, but may have equally robust procedures in place. Providing that their procedures are auditable and can be tested, this may be a requirement that can be relaxed.

Please also remember that GDPR whilst regulated, provide a set of guidelines which may be open to interpretation. It is worth making sure that interpretation hasn’t enabled lethargy around data security to creep in. It is also my suggestion that where possible the Authority passes the running of the systems data and data security to the platform vendor, who can be held to account for any GDPR, data and security breaches.

The Core Platform Configuration Layer: Onboarding – an overview of requirements

User onboarding is always a delicate affair. Do you ask the user for everything that is ultimately needed to cover every function of the app, or does one take a softly-softly approach and only ask for data as it is required? I take a personal approach to the systems that I deliver, and don’t ask for anything that isn’t absolutely required. I do not provide banking details until I need to, and only provide them after I have used a service for a few times and have built up a perceived level of confidence.

Likewise, we are advised to shield our Date of Birth, so anything with a DoB is also withheld for as long as possible. In my view anything that could thwart adoption should be very carefully considered, users can be quite harsh in terms of their critique, and one generally only gets a single opportunity to gain their trust and get them using your app.

There is of course more than one school of thought, but what I am suggesting is that you need to know your customer, when setting up these solutions, and ensure that wherever possible you are in tune with their demands, needs, and expectations. If one falls outside of these, one is likely to be punished, in terms of poor reviews, thwarted adoption, negative feedback, and even reduced app usage.

The platform must provide something positive to the user that they are not getting from other apps, and as such it must be easy to use, quick to use and provide data and information confidence.

Journey Parameters

When you start specifying your journey parameters, I would wager that most of the parameters that are listed will be on your hit list. You may even extend it to provide step-free access (coming in the next paper), or safer travels or leisure travel etc. Safer travel, for example, could avoid dark unlit paths or unsafe areas, or perhaps even slippery or accident-prone areas.

The rule of thumb is that journey planning is nothing more than a mathematical algorithm, that needs defined parameters to work. Anything that can be parameterised can at least in theory be included in the algorithm and therefore excluded in its results. If you were to identify a ‘best leisure route’, how would that be defined? If you wanted it to include walking or cycling, one would thereafter need to define whether it should only route you via parks or cycle paths, or safe and well-lit footpaths too? Would that still apply if it added an additional 30 minutes to your trip, and if not 30 minutes, what would the right distance/time be?

Likewise, one often sees cheapest, as a Journey Parameter. In-fact I’ve added this to the matrix, as it can be delivered if one defines what it means. Cheapest is a misnomer though. The cheapest way to go will be to walk, and that’s probably not what you were thinking. You would also need to take into account the ticketing options that exist. Is there any fare capping in place, has the user already reached a fare cap threshold, what concessionary fares are available, what is the user’s maximum walking distance and then walking speeds? This ensures that interchange points are accommodated accurately. The devil is very definitely in the detail, and it will need to be defined to ensure that you get exactly what it is you were hoping for,

Lastly, in this section we’re going to explore ‘Least Interchanges’. I have implemented a number of Journey Planning type solutions, and each of those has included the Journey Parameter Least Interchanges. If one travels frequently, particularly over long journeys, one will generally rather have a slightly extended journey over multiple interchanges. You’ve just got comfortable, and now you have to experience interchange anxiety, finding the right platform, making sure you make your connection, finding another seat to sit down at. And if its rush-hour, that’s never going to happen! While this is standard functionality in almost every journey planning platform I have implemented, there are some that claim this isn’t a user requirement. Even airlines use it to provide the option of indirect but cheaper flights, and that’s with guaranteed connections and guaranteed seats, and few use the feature. My advice is to make sure this type of functionality is not only requested, but fully specified.

Real-time Data Public Transport

Real-time location data is now pretty standardised. In the UK there is BODS Bus Open Data Service, there is GTFS and GTFS-RT, which is used pretty much everywhere else, but there are also other standards as well, Darwin for real-time train data, SIRi for messaging data etc. But they don’t necessarily provide you everything you need. For example, while BODS will provide real-time data, it is based on schedule data. If a bus is running on time and there is no variance you don’t necessarily receive any updates, the systems are expected to revert to schedule data. This sounds great, usable and problem free, but is it? What happens if a bus was not dispatched? There will be no data coming back to suggest that the bus was neither ahead or behind schedule, and the systems will assume that the bus is therefore running on time. In the US the systems generally are Computer Aided Dispatch Automatic Vehicle Location (CADAVL) which combines both the dispatching of vehicles with the true running location of the vehicle, preventing an occurrence of a non-running service being identified as running on-time.

Some operators do have internal systems where they manually enter non-running or cancelled services, but this isn’t their primary focus, which is of course dispatching buses. So this data can be a little incomplete, as the dispatcher will enter this after they have finished dispatching the vehicles they need to get out.

In the UK there is also no standard to capture non-running buses. This means that even if a transit operator is studiously entering the data, the DMP will be required to integrate with a number of different often proprietary systems to collect, collate and utilise the data that can be made available. This is, of course time, consuming, expensive, unstandardised, and unlikely to be made available in either XML or through an API.

Real-time Data Private, Active and Shared

In most cases the infrastructure provider, the micro mobility provider or the shared services provider will provide an API capable of interrogating service availability. This can be used within the DMP to indicate with some sense of optimism whether an e-Bike, e-Scooter or a shared car is likely to be available when required, and as part of an integrated itinerary.

Unfortunately, this isn’t necessarily the same for e-charging, or even car parks. At present there are few parking facilities that rely on pre-booking, and the reason for this is understandable. Car parks generally charge by the hour or day, and it’s based on a first-come-first-serve basis. If one starts to introduce bookings, there are likely to be spaces booked every day by perhaps the more affluent, which are most probably underutilised. Car park operators can maximise their revenues through short-term parking around longer-term parking commitments. This enables an average day rate or duration to be 5-6 hours, and then filling the rest of the time for short-term parking needs.

At present there are no data standards around car parking, there are even fewer API’s available that can be used to book a parking space. There is the National Parking Platform (NPP) but this is based around parking payments, rather than space availability.

Other Data

When designing, specifying or building your DMP, you will need to also define what additional data you wish to be made available within your digital environment. It’s likely that you will decide on accessibility data, perhaps station facilities data, parking data, EV charging data etc. However, please remember that any data that is made available must also be kept current. As an example, while it might be a great opportunity to promote restaurants and coffee houses, there might be high churn, and therefore become a nightmare to maintain. You might decide to make parking data available, including number of spaces, opening hours, price of parking or accessibility at a specific location. The problem is that all of this could change and the data collected from whatever source might be erroneous to begin with.

While I passionately believe that the data that is made available can hold real value, the question that needs to be asked and answered is, does the perception of the value of the solution diminish if it is known and understood that the data could be erroneous? To combat this, one might decide to rely on crowd sourced data for updates, and this can be a cost effective and brilliant way of keeping data up to date, particularly if one implements rules around how data is updated, where data is only updated after verification by a number of different people.

This isn’t necessarily a prerequisite for your DMP. But get it right and this will offer uniqueness and a level of detail that is perhaps not offered anywhere else.

Coming up next

The next article will concentrate on three elements, public transport modal selection and personalisation, the introduction of active, shared and private modes and first-mile/last-mile service provision within a Digital Mobility Platform environment.

Other articles

Article 1: MaaS – what is it and how do we get it right? – available here

Article 2: The main building blocks of Digital Mobility Platforms (MaaS) – available here

Article 3: The heart of Digital Mobility Platforms: Journey Planning Configuration – currently reading

Article 4: Your personal travel buddy: Personalised journey planning explored – available here