Your personal travel buddy: Personalised journey planning explored

This is the fourth of a short series of articles that aims to better define the requirements, limitations, and pitfalls to avoid when delivering Digital Mobility Platforms (DMPs),previously referred to as MaaS, within a UK deregulated transport environment.

This article will concentrate on some core elements that elevate DMPs and help define their credentials over and above simple typical Journey Planners. We will delve into personalisation, identifying some of the modules necessary to provide a fully inclusive solution. It will also indicate how the nature of personalised service expectations are evolving and, to some extent, expanding.

Personalising your Platform

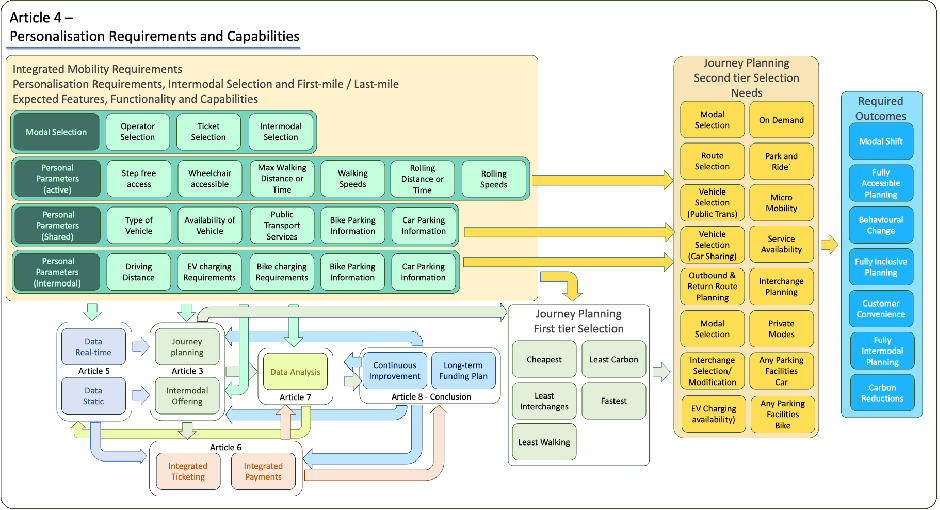

The following graphic provides an overview of some of the personalisation options that may become part of your DMP.

In my view, this element of your Digital Mobility Platform, provides you with the opportunity to truly deliver mobility innovation. Depending upon your business requirements this could be the difference between delivering a mediocre solution and a ‘best-in-class’ ‘platform destined to be successful and move digital mobility forwards.

Your platform will need to be tailored to your business emphasis, your regional opportunities, and the demographics of those you are trying to serve. For example, if your solution is being delivered in a more rural area, there might be emphasis on demand responsive transport, or intermodal integration. You may want to think about combining private and public transport, enabling better utilisation of mobility hubs, park and ride facilities, car parks or EV charging locations.

In more urban areas, more emphasis may be placed on micro mobility or personal bike integration with public services around transition hubs, or accessibility, particularly related to interchange points and service continuity, and perhaps more emphasis on integrated ticketing, fare capping and modal selection. In more rural communities due to economics and population densities, its reasonably unusual to have more than one operator serving a community, and therefore multi-ticket environments, fare capping and integrated ticketing may not be so important.

First, what do you want to achieve?

But before one starts to define any of these capability requirements, its essential to assess the outcomes your organisation is trying to achieve and working backwards from there. The above graphic identifies some of the more common outcomes, such as modal shift, traffic reduction, carbon reduction, intermodal integration etc. But starting with a list of desired outcome, will help identify a list of prioritised requirements, data expectations and capabilities best served to meet those objectives. As discussed in the first article, a well-defined specification will deliver a successful product that meets your demographic requirements.

This article will explore just two of the options that you may want to consider in a little more detail: Intermodal Integration, and Accessibility. These are perhaps the most complex modules to define, prepare and deliver, and while this article might identify requirements and an approach, much more detail and significantly more work will need to be undertaken to scope your individual requirements.

Intermodal Integration

Delivering an integration between public and private forms of transport is complicated. It may require integration with car parks, park and ride locations, mobility hubs, EV charging points, bike storage, as well as a wealth of additional data at these transient locations, such as facilities, pricing, service availability, interchange points etc. If one is striving for modal shift, I suggest that one should also take account of travel times, and travel time variability, which can only be achieved if one has access to a real-time road-based travel data as well as a body of historic data from which to calculate travel time variability from.

One should also consider what additional data may want to be made available to further support the consumer. Opening and closing times, price, public transport availability, micro-mobility service availability, location address etc. While the outbound trip is generally reasonably simple, with the exception of supporting the user to determine their preferred maximum private distance to travel, what additional support should be offered to the user by default to help them make their return journey? The following three options are generally considered:

- Should the DMP store the location, identify the date and time that the consumer will be heading back, identify the location(s) from which they would be coming, and then check service availability? The DMP could then perhaps keep them informed about service updates, disruptions, ticket expiry, and provide notifications when their last options of getting to their car or bike is within a user defined threshold?

- Should one provide no information, other than perhaps a disclaimer screen telling the user that they are responsible for finding their own way back to their car or bike?

- Should one be able to store their cars position as part of their favourite places, enabling an efficient way to navigate back? You could perhaps provide push notifications of closing times, and general travel times, but ultimately pass the responsibility of getting back to a user’s vehicle on their own shoulders? If choosing this option, it may be an additional personalisation option to provide a push notification containing the latest itinerary to get them back to their bike or car.

Accessible and step-free planning

Core to all our policies is equality – everyone should be able to travel. Accessibility isn’t necessarily just about step-free or wheelchair friendly planning, it could be to support the more ambulatory impaired, to help and provide support for a parent and child, with or without a buggy, it could be to better support working animals and their auditory or visually disabled carers, or it could be to better support the neurodiverse. Each of these different groups understandably will require different services and features. Most of these will require a level of data that probably doesn’t exist, or at best only partially exists, and some of this functionality or these proposed elements might not yet have been delivered anywhere. As a result, there will be challenges ahead.

It might also be a good idea to get countenance and backing from support groups that can tell you their explicit needs, but beware everyone is different, and everyone will potentially have different requirements. I recall delivering a solution previously where it was assumed that step-free access and wheelchair accessibility were essentially one and the same. Yet, when testing the solution we were told by one wheelchair user that they were quite capable of going down one or two steps, another user from the same group that was unable to navigate a step of even 25mm. This demonstrates the level of personalisation flexibility that is necessity to deliver within your DMP.

Issues with delivering these types of capabilities

You might think that all of this is new, but in reality, in 2001 when the first multi-modal web-based Journey Planner was launched, in London, it already took account of not only all modes of public transport, but also routed you to a taxi to accommodate last-mile solutions. Whilst some of the following functionality is no longer available, it also included step-free access, notifications of the health of lifts and escalators, facilities information, such as locations of any steps, ticket machines, restrooms and emergency maps for emergency services. It included a wealth of accessibility and disabled information much of which was then collected by hand, but has since become a reasonably standardised approach for such data.

Our transport and technology landscape has changed dramatically over the last two and a half decades, to include modes such as e-Bikes, e-Scooters and Battery Electric Vehicles (BEV’s) and, from a technology point of view, we now have smart phones, mobile apps, interactive voice recognition, artificial intelligence, application programming interfaces (APIs), as well as a wealth of transport related data standards that just didn’t exist back then. Despite these technological improvements, with one or two notable examples, the systems capabilities have not – in my opinion- kept abreast of the evolving business and passenger demands.

When contemplating delivering some of these features, it’s important to understand which services you are going to deliver, where the data that will support these services will be coming from, and which features will be made available. You should also consider how you manage with more data following on in future, by planning a programme of continuous improvement. It would also be worth working with UX/UI specialists to identify how such features should be presented to a user to ensure that they are as simple as possible while providing the flexibility to be enhanced as better data becomes available.

Non-standard or guaranteed data

There seems to be reticence by both platform providers to not include data that is neither standardised nor guaranteed to be correct. Let’s explore this in a little more detail. Is it better to provide no data, or the data that is available, even if the data that is available may be incorrect on occasion?

This will need to be a business decision. The problem is that no data is correct 100% of the time, and we are delivering what are generally considered very complex platforms. It will be impossible to provide correct information, correct itineraries, correct arrival times, correctly identified cheapest travel options, or quickest options, or safest options all the time. Digital Mobility Platforms are real-world solutions using real-time and, in some cases, predictive data. Road congestion might be worse than expected, vehicles will break down, points will fail. And, as a result, customer provided data cannot be 100% correct all the time.

There are additional data collection options that can also support your goals. I have used temporary workers to collect data to good effect, and Waze has taught us that crowd sourced data can provide quality and consistency enabling updates to be used with limited latency.

Knowing that data is and will always be potentially erroneous, the question to be asked is: would more personalised journey planning options be generally helpful, even if it is known, understood and accepted to be erroneous on occasion? In my view it is better to provide the data that is available, making sure the consumer knows that it could be inaccurate on occasion, and enabling the user to make their own informed decision.

Suffice it to say that with very few exceptions there is already sufficient data or data collection processes to deliver almost all the functional elements to accommodate a best-in-class Digital Mobility Platform that will meet and exceed your consumers expectations.

Coming next

The next article will concentrate on data, including availability, standardisation and gaps.

Other articles

Article 1: MaaS – what is it and how do we get it right? – available here

Article 2: The main building blocks of Digital Mobility Platforms (MaaS) – available here

Article 3: The heart of Digital Mobility Platforms: Journey Planning Configuration – available here

Article 4: Your personal travel buddy: Personalised journey planning explored – currently reading