MaaS – what is it and how do we get it right?

Over the next weeks and months, I aim to write a series of short articles that will try to help define the anatomy of MaaS, and how MaaS can be delivered successfully particularly in a devolved and sometimes disjointed transport environment, as is frequently found in the UK.

The objective of the following series of articles is to provide an overview of what MaaS needs to be, as well as develop a basic blueprint of how successful MaaS deployments can be delivered in a UK (or similar) environment. This will include the basic building blocks or elements needed to be included, the pitfalls to try to avoid, the lessons I have personally learnt from the delivery of a wide range of journey planners, real-time information solutions, passenger information systems, first-mile/last-mile solutions, ticketing and payment systems that I have been responsible for implementing both here in the UK and abroad.

This first article will discuss a few of the high-level lessons learnt, future articles will start to discuss in more detail the anatomy of MaaS, the basic building blocks that you might need to be successful, but each will try to identify lessons learnt in somewhat more detail. Future articles will also discuss what success looks like, and some of the measures and metrics that could be used to better demonstrate success.

What is MaaS?

Ask ten people what they expect from their MaaS solutions and you’re likely to get more than ten different answers. It’s such a poorly defined concept, which differs from region to region, that it’s difficult to convey concisely. At this point even the name of MaaS has been over used or become synonymous with financial uncertainty, where we have seen some of the larger MaaS players leave the ecosystem.

Some may ask – what’s in a name? The reason the name is truly important is because MaaS platform providers offer very different definitions to each other, and their white label capabilities vary massively from one to the other too. For example, MaaS could mean anything from the implementation of a simple deep-link, to a sequential purchasing process requiring a user to individually select every ticket they need, without integration to the results of the trip planner. Some would say this is MaaS, others may not.

The devil is in the detail and without proper definition, it can be unclear what an authority is purchasing. For local authorities, it is essential that they understand fully what is being proposed. I often prefer the term ‘Digital Mobility Platform’ (DMP), but will use both DMP and MaaS throughout.

MaaS: The story so far

Successful MaaS solutions do exist around the world, they were first introduced in Finland, which has a pedigree in delivering innovation around transport, but have since been implemented in Stockholm, Gothenburg, Sydney, Singapore, and various other places. Several attempts have been made to implement MaaS solutions in the UK with various degrees of success. Perhaps the best example in the UK thus far is Breeze in Solent. Breeze was delivered as part of a Future Transport Zone (FTZ) trial programme with a fixed timescale, and is now in the process of being wound down.

Both TfWM and TfGM are both currently delivering some elements of MaaS with more capability likely to be delivered over time. Nottingham and Derby are about to go live with their platform provider, Trafi, who have also won contracts with Kent, and WECA are about to go live with a new solution built on the Mentz platform.

Car vs MaaS?

In my view one of the pre-requisites of MaaS, or as renamed Digital Mobility Platforms, is to encourage modal shift – getting people to at least consider using public transport over their trusted and most loved jalopies.

Simply, we must offer a better solution to car travel. That’s not to suggest there isn’t a place for cars, and that the need for car travel varies from region to region or person to person. I personally live in rural Lincolnshire, and if wasn’t for a car, I’d have virtually no capability to get anywhere of note.

In developing our next generation mobility platforms we must include personalised options allowing users to see where it is cheaper, quicker or more carbon friendly to travel. There may need to be encouragement through gamification, or perhaps ease of use through integrated intermodal journeys.

And this may even include encouraging users to travel to transport hubs using their trusted steed, and then continuing their journeys using public transport or micro mobility offerings. If one of the primary reasons to deliver MaaS is to encourage modal shift then there must be some support offered to the car driver to encourage them to shift from their primary and preferred travel choices.

How do we get it right? What are the challenges?

There are clearly challenges associated with the delivery of MaaS in the UK. So, what went wrong with past implementations and how could they have been more successfully delivered?

1. The tech challenge

The first thing to mention is that, given the size of the MaaS market compared to the wider technology sector, many of these systems may be defined, delivered or supported by organisations that may not have prior experience of delivering these platforms before. MaaS is complicated and brings together ticketing which is complex in its own right, payments which is also hugely complex, real-time public transport data, static public transport data and a wealth of information, data exchanges, application programming Interfaces (APIs), deep links, data exchange capabilities and a plethora of other systems, services and data.

These types of solutions require hundreds of data sources to be consumed, some of these are static, some relate to branding, some are dynamic such as real-time disruption data. Depending on your MaaS approach you may also require hundreds of API integrations. But unless one has in-depth experience delivering these, there is likely to be a knowledge gap, which will lead to larger team compliments and exponential cost increases as you recruit new expertise.

2. No region is identical

The second issue is that no two MaaS solutions can or even should be expected to be the same. How could they be? If one considers each regional entity, they will each have different transport operators, and therefore different ticketing systems. Each is likely to have a very different approach to payments integration, each will have different challenges around data ingestion, data availability, look and feel and even basic functionality.

There will also be different user personas across different areas. More rural communities will perhaps have more emphasis on on-demand services or shared services, while locations with high population densities with more integrated public transport services may focus more on micro-mobility to fill the first-mile or last-mile gaps.

3. Getting the specification right

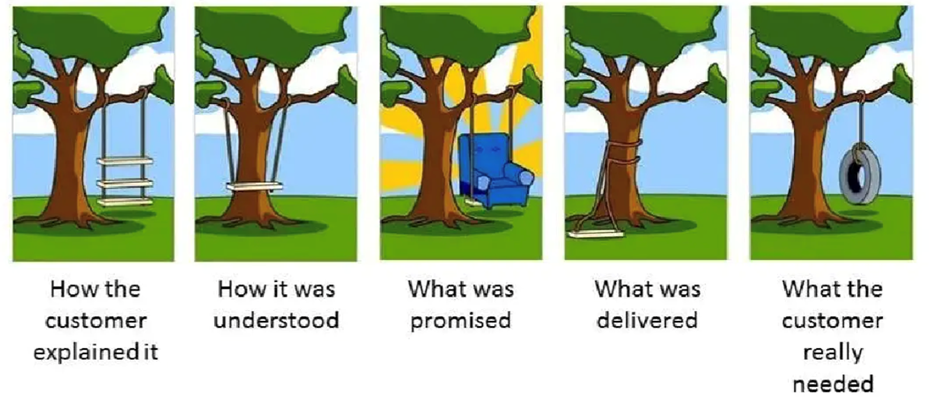

The third area that must be explored is the specification. If hindsight has taught us anything, it is that specifications need to be even more tightly defined. Failure to define a tight set of requirements essentially sends the message that the authority doesn’t really know what they are trying to achieve, what their unique objectives are, and what the problem is that they are trying to solve.

In the case of Nottingham and Derby some suppliers suggested the specification as issued was undeliverable and unachievable, but in this case, there was an experienced team in place that had undertaken due diligence, had carefully considered their business and user requirements and had a clear set of objectives. As a result, they knew that there were platform providers that both understood MaaS, had a track record for delivering solutions that would meet a good percentage of the requirements, and would most likely be able to deliver some of their stretch goals that would help to move MaaS to the next level.

An ill-defined specification is likely to lead to a bare minimum solution, that is unlikely to meet your organisational aspirational needs. Or the needs of your customers, and will could become another MaaS missed opportunity statistic.

4. The Procurement Lifecycle

We must also acknowledge that another issue is the procurement lifecycle.

Authority procurements take time and the more complex the procurement, the more time they take with the authority needing to fully brief their procurement, legal and IT teams. Complex procurements often need more rounds of more arduous scoring cycles, longer question and answer cycles, updated requirements to address questions, and the request for a Best and Final Offer (BAFO) which again will need scoring.

It’s also suggested that the authority always requests at least one full day with each supplier to demonstrate their system in detail based on the authorities specific requirements and expectations. To ensure that the authority gets the best from this time with the supplier, the supplier will need to be given reasonably detailed instructions about what the authority wants to see, hear about and to be demonstrated. Again, local authorities will need to be clear about what they want to see from their systems.

5. Last but not least – the long term funding plan

Many systems fail after implementation due to lack of long-term financial security. It is suggested that authorities identify a long-term plan to not only provide the ability to maintain and support their systems, but also identify funding sources that will provide a program of continuous improvement in line with changing user, business and regulatory needs.

While many platform providers will suggest advertising revenue, or a percentage of ticket sales, the foremost is generally frowned on by travellers and customers, and the latter may be unpalatable to transport operators. We need to be open to alternative approaches, and perhaps look at where successful solutions that have been delivered both here and abroad. In some areas sponsorship has been quite successful, in others the business community has been actively engaged to better support modal shift, whilst increasing public transport ridership. But going into MaaS without a long-term funding plan is perhaps a little reckless.

In my view one real barrier to MaaS in the UK is our own regionalised approach. While MaaS systems can be delivered regionally, this pre-supposes that the region is essentially self-contained – it becomes an island. This of course isn’t true. If a user wishes to travel across multiple regions, they will still need to revert to Google, or download multiple apps to stitch together itineraries and other basic ticketing information.

While users are required to do this, will MaaS ever be truly successful? We need a more stitched-together solution that encourages different MaaS platform providers to work together to provide a back-end-automated solution. This could quite easily be delivered using APIs, but it would require platform providers to work together, define the systems and services that should be integrated, and develop a new standard which does not give unfair advantage to one or two providers.

It may surprise some to know this isn’t actually new, back in the early noughties there were XML protocols and standards developed for data exchange between journey planners – at that time it was called JourneyWeb.

Coming next

The next article will concentrate on the main building blocks of Digital Mobility Platforms, how different platforms must work harmoniously together, what the integration points are, what levels of integration are available as opposed to those that are required, and the potential pitfalls that authorities should be aware of. It will also cover why DMP’s are more arduous to deliver in a devolved and UK esque devolved transport environment.

Other articles

Article 1: MaaS – what is it and how do we get it right? – currently reading

Article 2: The main building blocks of Digital Mobility Platforms (MaaS) – available here

Article 3: The heart of Digital Mobility Platforms: Journey Planning Configuration – available here

Article 4: Your personal travel buddy: Personalised journey planning explored – available here